In the past,

I blogged at What Would The Founders Think? One of my articles was

titled, “The

Founders Fear.” The article asserted that the Founders architected a

limited government because they feared unrestrained power. This was written way

back in 2011, but I received a scolding from a troll last week. Reeve wrote:

“The infant periods of most nations are buried in silence, or veiled in fable, and perhaps the world has lost little it should regret. But the origins of the American Republic contain lessons of which posterity ought not to be deprived.” —James Madison

Sunday, February 23, 2014

Monday, February 10, 2014

Why did the colonists revolt?

In the five centuries following the Magna Carta (1215),

Englishmen had gradually gained individual rights, so that by the late

eighteenth century, the English were beginning to exercise a degree of

self-government. The King and nobility still wielded substantial power, but

Parliament had gained increasing authority, especially the elected House of

Commons.

Toward the end of this period, the opinions of those outside the aristocracy were increasingly influenced by the Enlightenment, an intellectual movement of the seventeen and eighteenth centuries. Enlightenment thinkers began to challenge existing religious, government, and social norms, and pushed for additional individual liberty and the free exercise of natural rights. They argued that mankind not only had a capacity for self-government, but that it was a natural right. Through an evolutionary process, Englishmen grew to enjoy an ever-increasing say over who made the laws that governed their lives. That is, those Englishmen who lived in England. If an Englishman happened to live in one of the British colonies, he was still a mere subject of the crown with no representation in Parliament.

Toward the end of this period, the opinions of those outside the aristocracy were increasingly influenced by the Enlightenment, an intellectual movement of the seventeen and eighteenth centuries. Enlightenment thinkers began to challenge existing religious, government, and social norms, and pushed for additional individual liberty and the free exercise of natural rights. They argued that mankind not only had a capacity for self-government, but that it was a natural right. Through an evolutionary process, Englishmen grew to enjoy an ever-increasing say over who made the laws that governed their lives. That is, those Englishmen who lived in England. If an Englishman happened to live in one of the British colonies, he was still a mere subject of the crown with no representation in Parliament.

|

| Benjamin Franklin before Lords in Council in Whitehall Chapel |

Labels:

Benjamin Franklin,

first principles,

founders,

founding,

founding fathers,

founding principles,

freedom,

government,

government theory,

political science,

revolt,

rights,

washington

Friday, February 7, 2014

Our American Heritage

The colonists did not only revolt against taxes; they

revolted to stop the British from taking away the self-governance they already

had been exercising since the earliest colonization. The crown appointed

governors for the colonies, but over three thousand miles of ocean in the day

of wind-powered ships gave ordinary Americans more freedom than a minor noble

living in Bristol, England. (Connecticut and Rhode Island even elected their

own governors.) Americans bristled over dictates from Parliament because

colonial legislatures had been exercising substantial power for well over a

century.

|

| Plymouth Plantation Today |

Labels:

Benjamin Franklin,

colonists,

economics,

economy,

first principles,

founding principles,

government,

government theory,

john locke,

liberty,

political science,

property rights,

revolt,

rights

Tuesday, February 4, 2014

A Time of Civil Debate

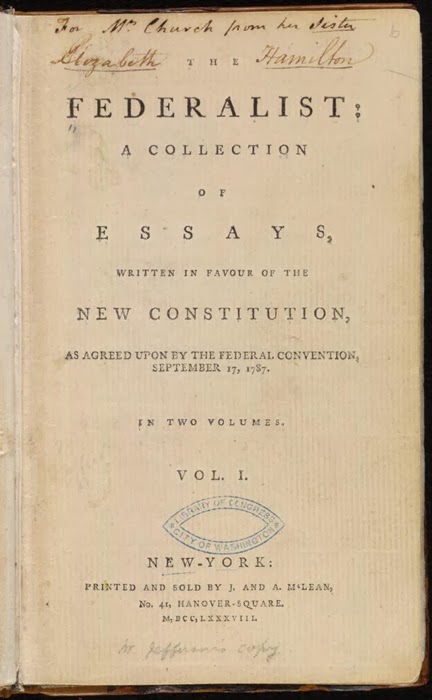

A rowdy debate consumed nearly everyone in the United States

between the Constitutional Convention and ratification. The population of the

country was about four million and possibly a quarter of that

number were activists during the Revolution and founding. What did people think

about a constitution written in secret? We don’t have to guess. A prodigious number of

articles and pamphlets were published by proponents and opponents.

Sunday, February 2, 2014

Can Tempest at Dawn be taken seriously?

Tempest at Dawn is

a novelization of the Constitutional Convention. As a novel, it is not bound by

the rigorous constraints of a nonfiction history book, but it does not deviate

from the historical record except for modernizating language, re-sequencing of debates for logical presentation, and attributing a few speeches to a different delegate

because that person was already established as a character. It’s confusing to

tell a story with more than sixty characters, so I had to choose a

representative sample and occasionally attribute to them the words or actions

of others.

.jpg) |

| The real story of our nation's founding. |

James Madison’s

comprehensive convention notes provided a solid framework for what happened inside

the locked doors of the Pennsylvania State House. The events outside the State

House occurred, but literary license was used because there were very few recorded

details about them. For example, Franklin’s dinner, the John

Fitch Steam Boat demonstration, horse races, and George Washington having a carriage built were all outside activities during the convention. The Fourth of July celebration happened pretty

much as portrayed, and delegates did witness a two story house being moved down

the street.

Other than speeches, conversations were speculative, but based to

a large degree on what must have been discussed in private meetings to shift

the votes and opinions expressed in the proceedings.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)